Rules to Give By Can Be Hard Habits to Break

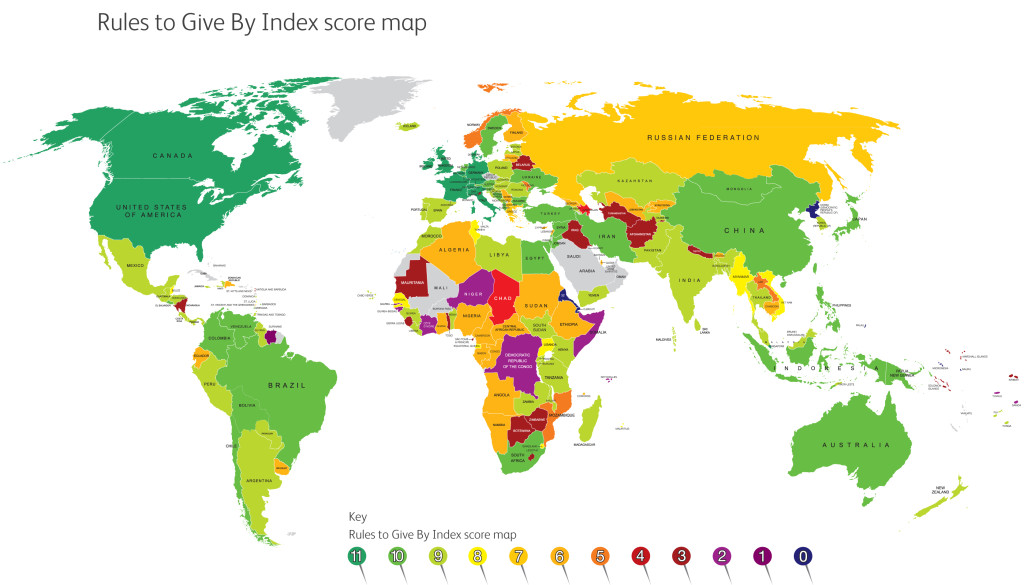

Recently, TWI grantee Nexus Global Youth Summit put out a study on global tax codes that encourage or prevent individual and organizational giving. It’s called “Rules to Give By” and it’s fascinating. The findings were by and large that 77% of the countries indexed do indeed provide tax incentives for giving, a heartening fact. I am 100% behind Nexus’ Global Campaign for a Culture of Philanthropy that endeavors to “shift the culture of philanthropy to an aligned and impactful practice by establishing and applying standards for the practice of philanthropy.”

I was immediately struck by an approach that looked at tax codes as the “rules” individuals and organizations “give” by. When I first heard the phrase, the rules that occurred to me seemed more like social codes or institutional habits. Tax codes are, of course, legally enforceable policies that serve to govern financial activities, so it’s a stretch for me to jump from here to funder habits. But, for imagination’s sake, here are some examples of institutional giving habits that seem prevalent for many foundations, particularly staffed foundations:

- They feel they must focus on a specific issue area and not go outside their box (and then often revisit those areas with new strategic plans every 5-7 years).

- Regardless of size, due diligence and grant-making means setting up overly bureaucratic, time intensive, and onerous application and reporting practices.

- They take the minimum 5% legal payout requirement as the maximum in order to exist in perpetuity.

As Carrie Avery recently noted in an interview with TWI staff, there sometimes appears to be little imagination in the sector. With so few actual codes foundations in the U.S. are legally obliged to follow, “there could be less bureaucracy and more creativity,” she muses. We wondered why there aren’t thousands of different models of giving in the sector, and why so many institutions are cookie cutter versions of each other?

There seems to be a set of invisible yet well followed rules to give by in the imprint of an American foundation. Best Practice, you may challenge? I’ve long been suspicious of the idea of Best Practices – because what is best in a given context, with a given purpose and constituency, in a given time frame is specific to a set of conditional factors. Factors that are often in flux.

My guess? It is uncomfortable to face inequality. It is uncomfortable to give up power. It is uncomfortable to give up the privilege of being the one to define the problem, propose a solution, and set up the rules of the giving game. Many giving organizations are organized around a charity vs. partnership frame. When the “rules to give by” reinforce the subjects (grantees) are receivers of resources (and strategies/solutions of the givers), not powerful creators of solutions and strategies for the problems they themselves face, it actually mimics the inequality that the “giving” is intended to re-balance.

Some recent social science research makes the intriguing argument that economic privilege literally alters the brain to create a lower threshold for compassion, making wealthy folks LESS likely to give. So my guess is that folks follow the invisible (and founded on a “charity” mindset that reinforces inequality) rules of the U.S. giving road because it requires less.

Less intensity than actually asking those you want to help HOW they want to be helped – which would require, you know-conversations, real talk, giving up a bit of power/privilege, and relationship over time. Less intensity than asking how to boldly go about using money to make positive change – which can mean admitting to not knowing, admitting to the possibility of failure. It seems like the easier road.

The wisdom in rebalancing inequities through a more creative and collaborative practice of giving is that it actually creates far more effective solutions led and sustained by those who experience inequities first hand.

The difficulty in it is that it means being present to and with the discomfort that structural, social, economic and political inequality brings. I would argue that this is where the work truly is. And that digging in here, and practicing equity in the ways that we give as well as discernment about what efforts towards equity we support, will see benefits far beyond a tax code that encourages giving. Although – we’ll take that, too!

To see the full Nexus Rules to Give By Index Report, go here